A lawyer, a road inspector and a cardiologist walk into a coding competition. So did I. This is no longer a joke.

I apologized for not being a coder. Most answered: me neither.

We all built software last week. None of us should have been able to. A US lawyer cracked California's housing crisis. A Belgian cardiologist's code helps him fix hearts. A guy in Uganda automated road inspection. And me — a man who hunts bad intentions in fine print and built a tool that does the same.

13,000 people applied to Anthropic’s Build with Opus 4.6 coding competition. 500 were selected including yours truly. 277 made an actual product last week (see full list of all projects at bottom). Could this happen to you too? Some say coding is largely solved. You can now tell a computer what to build in the same language you'd use to explain it to a colleague. Which is great news for everyone who's been explaining things to colleagues for years and getting nowhere.

But there's a catch. Domain beats syntax. You still need to know what to build, and when the machine got it wrong.

Over 21 million lines of code were written in six days. Yesterday, the winners were announced in a private session with Boris Cherny (head of Claude Code). Cat Wu — co-creator of Claude Code, the person who helped build the tool that all teams used — had sent her scores before a courthouse claimed her. Actual jury duty. The legal kind.

I loved discussing nerdy stuff with her and others from Claude. I'd discovered that asking an AI to write its own instructions often produces better results than telling it what to do — and wanted to know why. Cat Wu's answer is below (video).

I find the story in data. And if the story is bad, who started the fire. And yet there I am, in the project gallery, in the same list as a software engineer who pointed an AI fraud detector at 7,259 FEMA COVID contracts and independently flagged the company that shipped soda bottles as test tubes, and a developer whose Telegram bot fact-checks your mom's forwarded messages with six AI agents — including one whose only job is to tear the findings apart. Adrian Michalski built Silene Systems, a clinical workbench for rare diseases. He shipped a working app. His lesson: “I focused on shipping a product instead of focusing on the story and the demo.”

I keep scrolling through that gallery. Rxly.ai generates structured clinical notes that feed directly into EHR systems via FHIR R4. Think of it as an AI scribe for doctors. I became friends with some of the coders via LinkedIn. And apologized: sorry, I'm not a professional coder. Most answered back with: me neither. Those who were real coders never answered.

(INTERMISSION) Become member in February and you can win :

🎁 3x Perplexity Pro annual subscriptions , worth $240 each

🎁 1x You.com Team plan annual subscription, worth $300.00

To win? Just be a paid subscriber this month. That’s it. Already subscribed? You’re in. Not yet? Fix that before Feb 27th 2026. I’ll draw winners on Feb 28th 2026 .

The winners

CrossBeam won first place.

Mike Brown is a California personal injury attorney. Not a software engineer. Not a computer science graduate. A lawyer who learned some code in the past year. His opening line in the demo: “Everyone thinks California has a housing crisis. We don’t. We have a permit crisis.”

The numbers back him up. Since 2018, California has issued over 429,000 ADU permits — accessory dwelling units, the granny flats and backyard cottages that are supposed to ease the housing shortage. Over 90% get sent back for corrections on the first submission. Each correction cycle costs weeks and thousands of dollars. A typical 6-month permitting delay costs $30,000 per project.

Mike’s friend Cameron builds ADUs for a living. Mike watched him fight through correction letter after correction letter — dense bureaucratic documents citing California Government Code sections 66310 through 66342, referencing municipal code subsections that differ from city to city. Every correction requires cross-referencing the blueprints, the state law, and the local amendments. It’s research. Tedious, cross-referential, multi-source research.

Sound familiar? It’s what I do for a living. Except I do it with documents that are intentionally misleading. Cameron does it with documents that are accidentally incomprehensible. Same problem, different league.

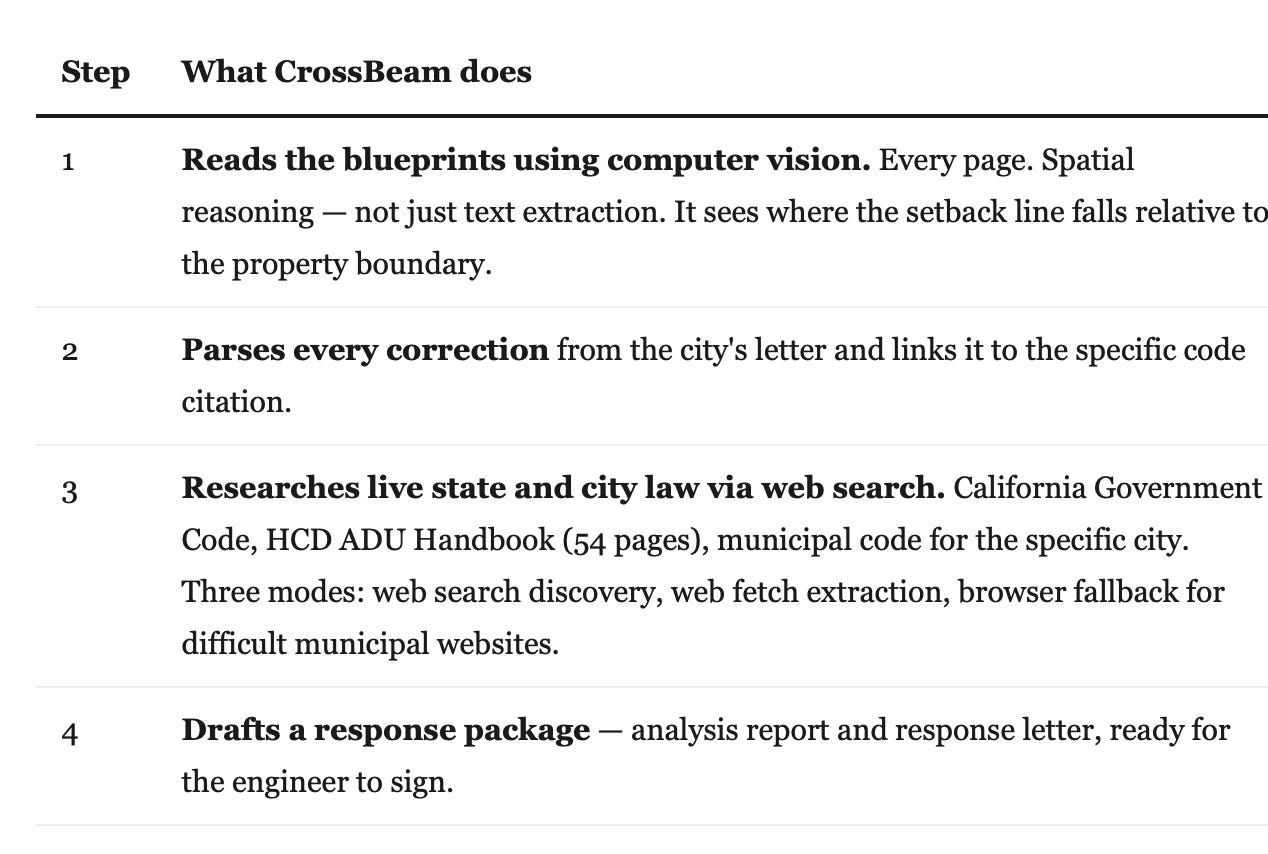

So Mike built CrossBeam. You upload your correction letter and your construction plans. What happens next is remarkable:

The architecture: 13 custom “skills” — not hard-coded logic, but structured reference documents the AI learns from. A 28-file California ADU knowledge base covering the full handbook, decision tree routing, threshold tables for heights, setbacks, parking requirements, fee structures. Each agent runs in an isolated sandbox because a single correction analysis takes 10 to 30 minutes — longer than any serverless function allows.

An attorney. Built a multi-agent AI system. With isolated sandboxes, real-time database sync via Supabase, parallel skill execution. In six days. The mayor of Buena Park, Connor Trout, showed up in the demo video: “By 2029 I need over 3,000 new homes permitted, including ADUs. Last year we had under a hundred. It’s not doable with our current staffing levels. We need this software.”

Boris Cherny — the man who created Claude Code, the tool Mike used — watched the demo and said: “I loved the user focus on this one. Talk to a user, what do they want, let’s build that. Talk to another user, they want something else, let’s build that. That’s really the way the Claude Code team builds.”

Second place: coding environment for kids

Jon McBee built Elisa — a coding environment for kids. No typing. Children drag and drop blocks to describe what they want: a goal, a rule, a skill. Hit Go. AI agents build it. While the agents work, a teaching engine explains what's happening in age-appropriate language. The kid designs. The AI codes. The kid learns how. 39,000 lines. Built solo. In six days.

Third place : the cardiologist on the motorway

Michal, a cardiologist in Brussels calls his workplace the cath lab. It’s where you treat the heart. He’s done thousands of procedures. But he says the real struggle begins “the moment you leave the room.”Patients don’t understand their diagnosis. They don’t remember what the doctor said. They go home confused.

So on his commute to the hospital, he heard about the hackathon. “On the road is where my best ideas come to life.” A week and a few thousand kilometres later: a post-visit AI companion that explains your diagnosis, translates medical terms, analyzes your health file using Opus 4.6’s million-token context window, and acts as your own AI scribe — the same technology doctors are starting to use, but on the patient’s side of the table.

The fencer, the road inspector, and the musician

The other finalists are equally niche, in the best possible way.

FenceFlow automates fencing tournaments. Not the garden-fence kind. The sword kind. If a referee submits impossible score combinations, the AI catches it. Coaches get a multi-turn chat with Monte Carlo simulations to analyze matchups. Boris Cherny called it “a glimpse into the future” — personalized software for communities so niche they’d never get a commercial product. The fencing world. With AI-powered analytics.

Tara won the “Keep Thinking” prize. Built by Kiyunye Kazibwe, it analyzes dashcam footage of roads in Uganda to produce infrastructure investment appraisals. Upload a video of a drive-through, get: surface condition analysis using computer vision, road segmentation by roughness index, cost estimates for interventions, economic analysis with IRR calculations, and an equity assessment that identifies who will actually benefit from the road. A process that used to take weeks. Tara does it in five hours.

Conductor won “Most Creative.” A musician built an AI bandmate that follows their playing in real time — following chords, following energy — and produces accompaniment through Ableton Live. Not AI generating music. AI playing with a musician. The judges’ verdict: “The music’s great. It’s a bomb.”

A fencer. A road inspector. A musician. A cardiologist. A lawyer. A research specialist who reads fine print.

This is what some of the 277 projects in six days look like.

The one that reads your contracts

Somewhere in that gallery, between the infrastructure appraisers and the fencing analytics engines, is mine.

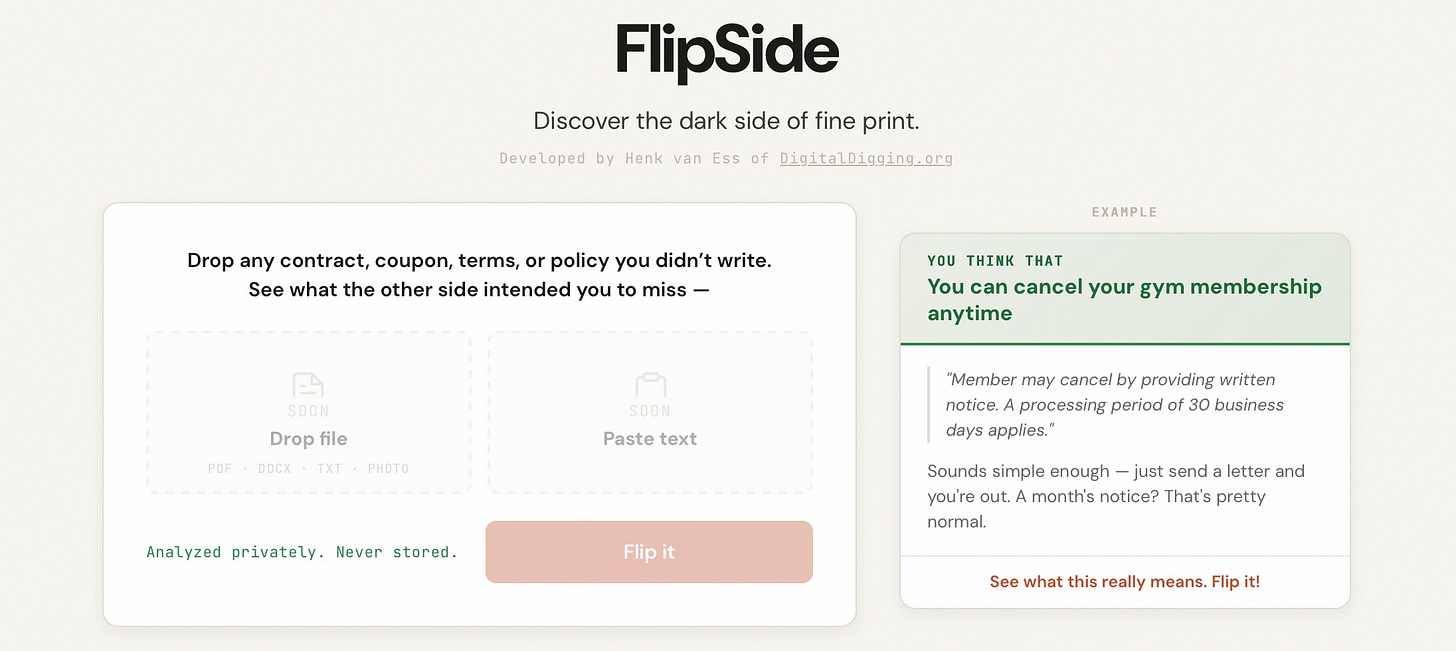

FlipSide. You know the problem. In 2018, researchers at York University and the University of Connecticut added a clause to a terms-of-service agreement requiring users to assign their firstborn child as payment. 98% missed it.

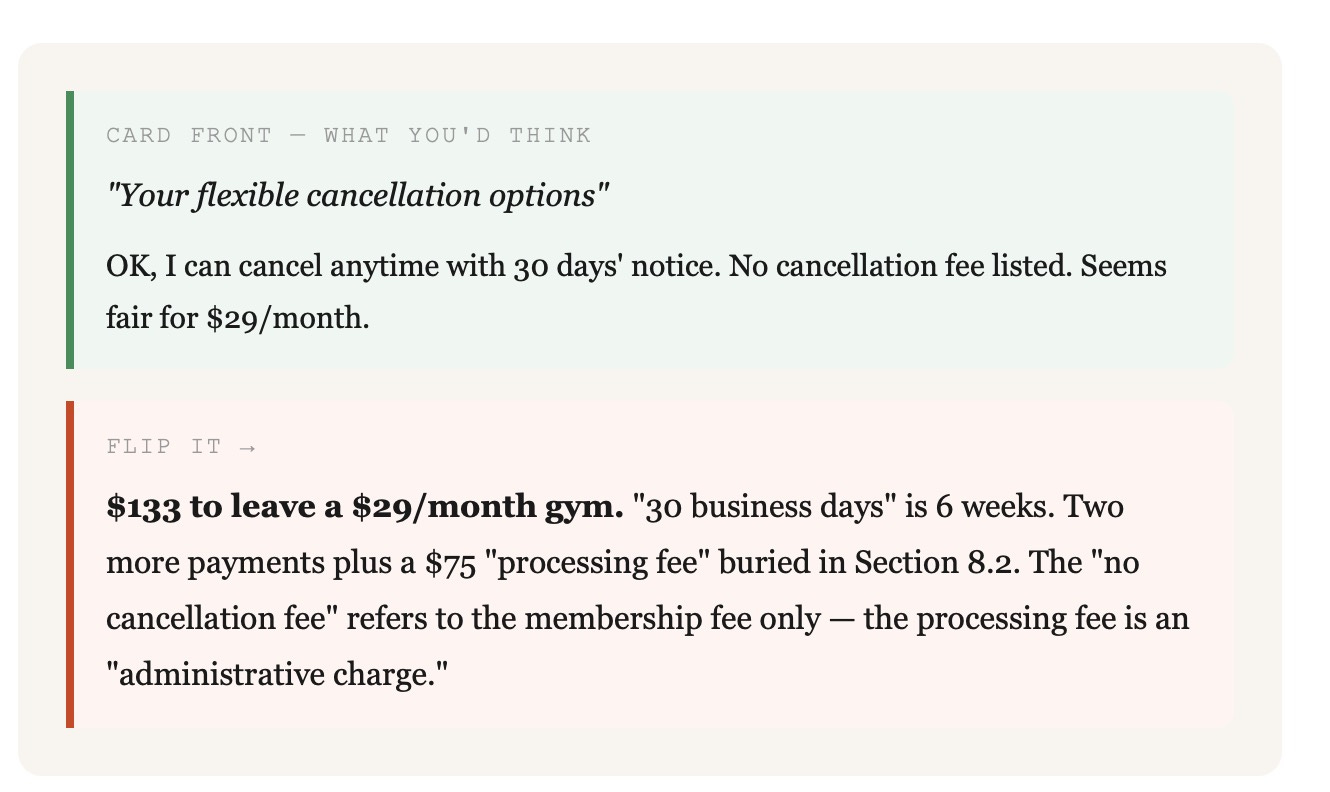

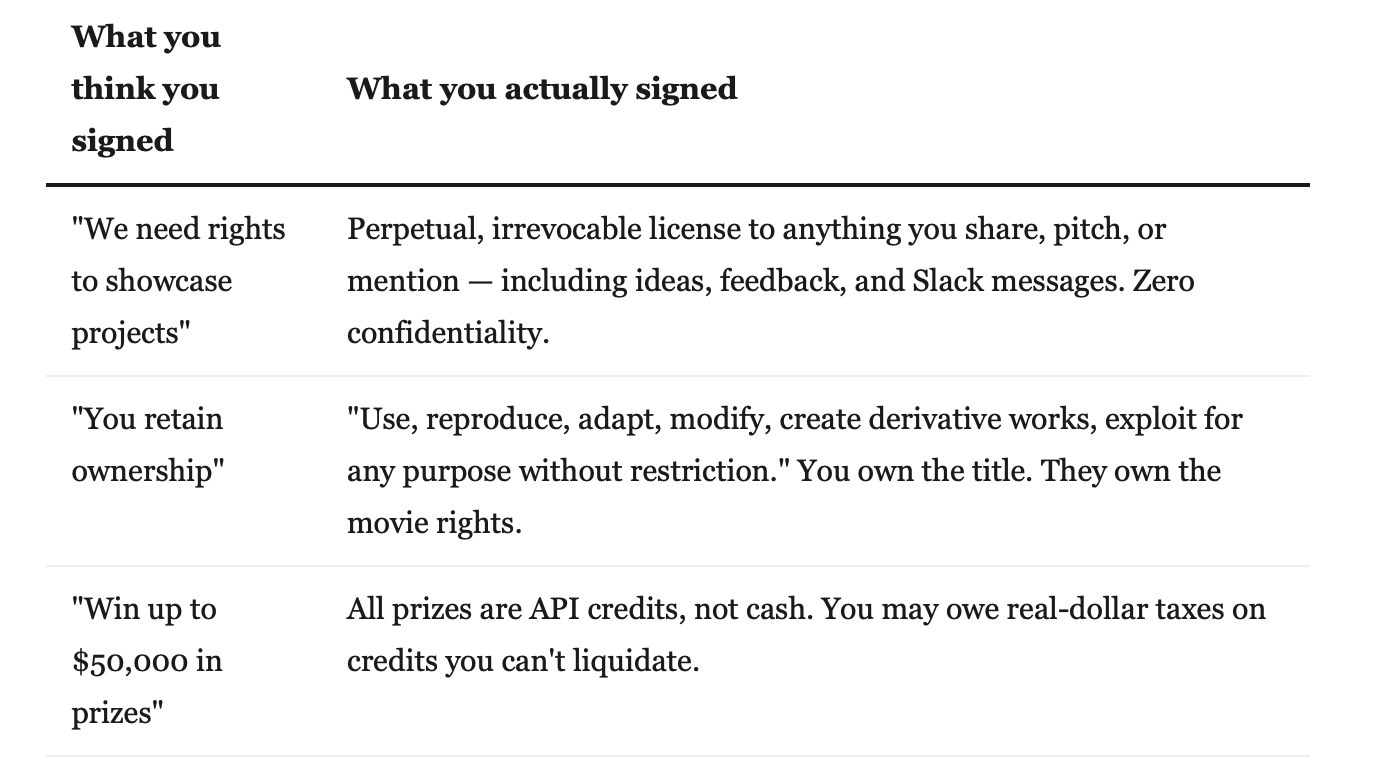

You upload a document — a lease, a gym contract, app terms, anything you didn’t write. FlipSide shows you two readings of the same clause. The first is how you’d read it: “Yeah, they just need 30 days’ notice, makes sense.” The second is how the person who wrote it reads it: 30 business days is six calendar weeks, you owe two more payments, plus a fee that isn’t called a fee. The clause doesn’t lie. Every word is accurate. The trick is in what’s missing: no cap, no appeal, no definition of “administrative charge.”

That gap — between what you think you read and what the words actually permit — is what FlipSide finds. Not “this will hurt you.” That’s a prediction. “This protection does not exist.” That’s a structural fact.

Day one was eight hours of conversation before a single line of code — teaching the AI how I think about researching documents.

The hardest part was stopping the AI from doing what it wanted to do: scare people. Every first draft came back with warnings. “This clause is unfavorable.” “This could cost you thousands.” Predictions. Opinions. Exactly the kind of subjective language I was trying to detect in the documents themselves. I was building a bias detector with a biased tool.

The fix: I stopped telling the AI what to find. I taught it how I read. Hours of conversation, zero code — just explaining what an omission looks like, how to use neutral language and how to be emotionally safe. I submitted a paper on the method to CHI 2026, the world’s largest human-computer interaction conference. The academic term is “adversarial sensemaking.”

But let me be clear about what I’m not saying. Mike Brown built a system that a mayor says his town needs to meet its housing targets. I built a tool that tells you your gym is overcharging you. The scale is different. The ambition is different. What is the same: neither of us is a professional coder.

The punchline nobody asked for

So I needed a document to test FlipSide on. Something I hadn’t written. Something I’d signed recently without reading. The hackathon waiver was right there. The rules of the contest.

FlipSide's cross-clause finding: “They can kick you out and keep your work forever. Subjective conduct policy plus unconditional IP license with no termination trigger.”

I built a lock-picking kit at the lock company’s own workshop, using the lock company’s own tools, and the first lock I picked was theirs. While the lock company was judging my work. Oops.

Boris Cherny: coding is largely solved

The same day the hackathon ended, Cherny — the man who created Claude Code — went on Lenny’s Podcast:

“I think at this point it’s safe to say coding is largely solved. At least for the kinds of programming that I do, it’s just a solved problem.”

— Boris Cherny, Lenny’s Podcast, Feb 19, 2026

Usual suspect, yes. But 277 projects in six days is not a sales pitch. It’s a body of evidence. And if he’s right, we’re heading to a place where people who hate technology can change technology.

He compared it to the printing press. Literacy in the 1400s: below 1%. Scribes — a tiny professional class — did all the reading and writing. Then Gutenberg. Fifty years later, more printed material than in the previous thousand years.

“I imagine a world a few years in the future where everyone is able to program. Anyone can just build software anytime.”

— Boris Cherny, Lenny’s Podcast

Cherny said the title “software engineer” will start to go away. The replacement: “Builder.” “People that have no technical experience can do exactly what you’re describing. Any time you get stuck, just like help me figure this out. And you get unblocked.” That's like finding out you've been speaking French your whole life. You just never went to France.

What I learned

What I learned is that domain beats syntax. Mike Brown didn’t build CrossBeam because he learned JavaScript. He built it because he’s a lawyer who understands California Government Code sections 66310 through 66342. Micha didn’t build Post-visit AI because he learned Python. He built it because he’s treated thousands of hearts and knows what patients forget the moment they leave the room. I didn’t build FlipSide because I learned Flask. I built it because I’ve spent twenty years reading documents until they confess.

Each of us had the same tool. The same six days. The same Opus 4.6 model. What differed was the domain. The problem we understood deeply enough to know when the AI’s output was wrong.

Because it does get things wrong. In my case, it produced biased prompts for the tool that was supposed to detect bias. It broke every parser by silently drifting from its output format.

I caught the errors. Not because I can read code very well. Because I can read output and notice what should be there but isn’t. An omission test — the same technique FlipSide applies to contracts — applied to the AI itself.

Coding is solved. What's not solved is knowing what to build and when the machine got it wrong. That's not a coding skill. That's domain. 277 teams had it. That's not everyone. That's not yet. But if you're a lawyer, a cardiologist, or a guy who reads fine print — your computer is ready when you are.

Links:

CrossBeam (1st place): github.com/mikeOnBreeze/cc-crossbeam

Hackathon gallery: cerebralvalley.ai — all 277 projects

CHI 2026 paper: “Sensemaking Against the Drafter” — CHI 2026 Sensemaking Workshop, Barcelona (later)

Try FlipSide: flipside.digitaldigging.org

Day one (8 hours, 0 code): How FlipSide Was Born

Disclosure: FlipSide was built with Claude Code (Anthropic) during the Build with Claude AI Hackathon. They gave me $500 free credits for their API for coding during the contest.

"I built a lock-picking kit at the lock company’s own workshop, using the lock company’s own tools, and the first lock I picked was theirs. While the lock company was judging my work. Oops."

Ha.ha... Absolutely hilarious !! Did they reach out to you after reading this ?

Thank you for the recap