They Droned Back

Young journalists expose Russian-linked vessels circling off the Dutch and German coast

Seven German journalism students tracked Russian-crewed freighters lurking off the Dutch and German coast—and connected them to drone swarms over military bases.

Let me walk you through what Michèle Borcherding, Clara Veihelmann, Luca-Marie Hoffmann, Julius Nieweler, Tobias Wellnitz, Sergen Kaya, and Clemens Justus of Axel Springer Academy for Journalism and Technology pulled off.

Just so you know, I’m familiar with them. I did a long OSINT training with them in Berlin. I can tell you: they went far beyond anything I taught them. The physical verification alone—chasing a ship across France, the Netherlands, and Belgium—that’s not something you learn in a classroom.

On the night of May 16, 2025, two ships were sitting in suspicious positions. The HAV Dolphin—flagged in Antigua & Barbuda—had been circling in Germany’s Kiel Bay for ten days. Not delivering cargo. Just loitering, 25 kilometers from defense shipyards where drone swarms had been spotted on three separate days.

Meanwhile, 115 kilometers away off the Dutch island of Schiermonnikoog, her sister ship the HAV Snapper had sailed out and parked in open water. It positioned itself exactly two hours before seven drones appeared over a Russian freighter being escorted by German police through the North Sea. It stayed there for four days and made silly circles.

That Russian freighter, the Lauga—formerly named “Ivan Shchepetov”—had visited Syria’s Tartus port the previous summer. Russia’s only Mediterranean naval base. Where Russian submarines dock.

Coincidence? That’s what the students from the Axel Springer Academy decided to find out. What followed was a five-week investigation involving leaked classified documents, tens of thousands of ship tracking data points, a 2,500-kilometer car chase across three countries, and—in a delicious bit of turnabout—their own drone flight over one of the suspect vessels.

“Wir haben zurück-gedrohnt,” they told their audience today during a presentation of the project. We droned back.

Here is the actual footage of the ship that the students droned, including more background. It’s in German.

The scale of the problem

Let’s start with the numbers that German authorities didn’t want public.

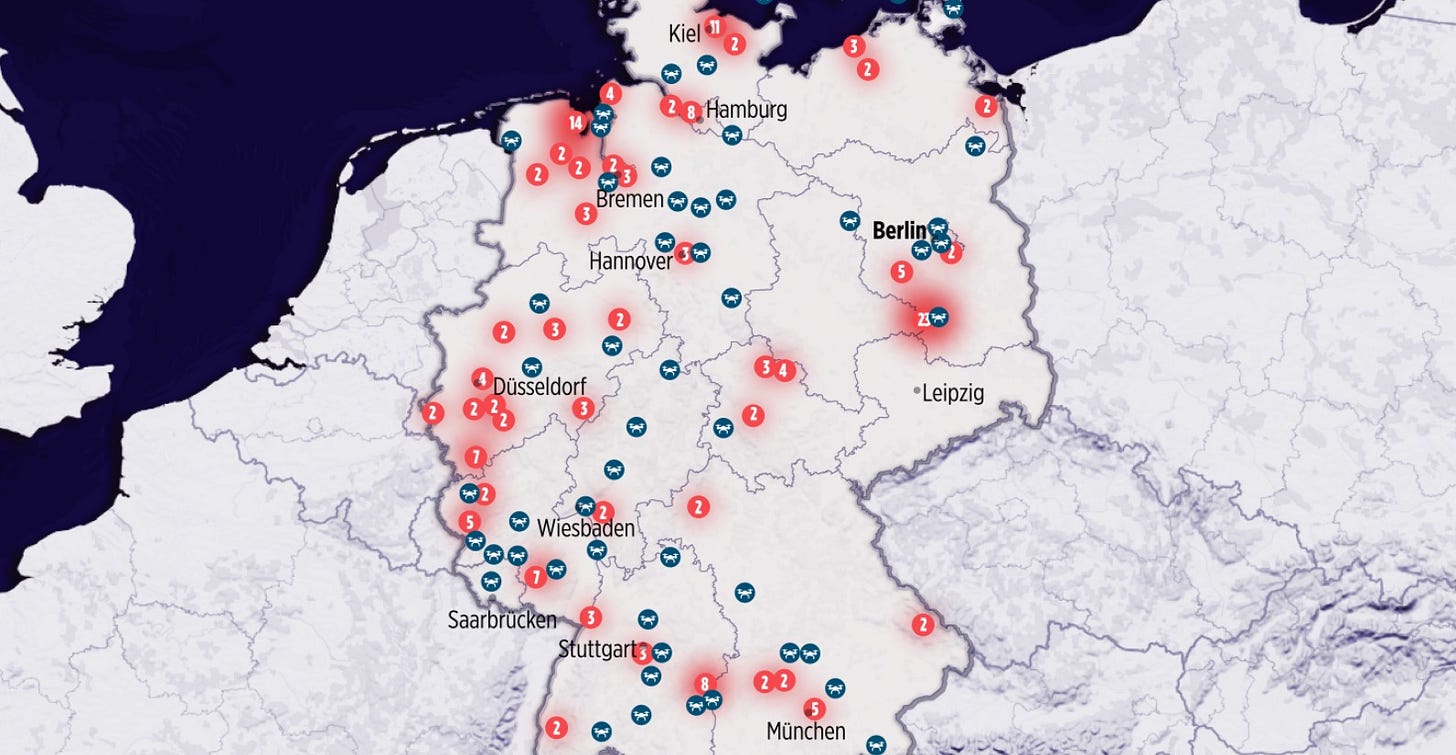

According to classified BKA reports obtained by the team: 1,072 incidents involving 1,955 drones in 2025 alone (as of November 19). Forty-five percent occurred in evening hours. Drone swarms flew “almost exclusively over or near military installations.”

In only 29 of 498 investigated cases could drone pilots be identified. In none of those cases were they state actors. In 88 percent of cases, authorities couldn’t even identify the drone type.

The BKA’s own assessment: “Individual incidents indicate complex operations drawing on larger financial and logistical resources.”

Translation: this isn’t hobbyists.

Munich Airport

October 2, 2025. First drone sightings around Munich Airport at 22:10. By 22:35, the airport shut down completely. No departures, no landings. Nearly 3,000 passengers stranded overnight.

October 3: same thing. Another shutdown. This time 6,500 people affected. Four hundred emergency cots deployed. Over two days: roughly 10,000 travelers disrupted.

Economic damage to Munich Airport: 6 to 8 million euros.

By October 2025, German air traffic control had logged 192 drone incidents—a new record. Frankfurt led with 43.

The Munich prosecutor’s office is investigating “dangerous interference with air traffic.” Against unknown perpetrators.

The pattern

The leaked BKA documents reveal a disturbing pattern: drones aren’t just buzzing airports. They’re systematically surveilling military installations—often during sensitive operations.

April 15, 2025: A drone overflies Werratalkaserne in Bad Salzungen at 9 PM. At that exact moment: combat vehicles were being delivered and stored for transport to Ukraine.

May 17-21, 2025: During the Bundeswehr exercise “Gelber Merkur” across four German states, more than 80 drone sightings over military sites and defense contractors. Almost exclusively in evening hours.

January 28-29, 2025: Multiple drones spotted over Schwesing airfield. At the time, Ukrainian soldiers were being trained there.

Q1 2025: Persistent overflights of US Air Base Ramstein.

June 4, 2025: Photo reconnaissance of Wilhelmshaven Naval Arsenal.

January 8, 2025: Drones flying in formation over a naval aviation squadron base in Nordholz.

It’s not just military bases.

February-March 2025: Three evening overflights of the LNG terminal in Stade. Two incidents at the adjacent seaport. Seven incidents over Wilhelmshaven Naval Arsenal. One pilot was identified: a 69-year-old German. No evidence of state involvement in that case.

May 4, 2025: A drone flew over Biblis nuclear power plant for five to ten minutes. An unknown vehicle drove up to the open facility gate. Search unsuccessful.

January 13, 2025: Multiple drones spotted over a chemical company in Marl starting at 8 PM. No drone models identified. No suspicious persons or vehicles found. Authorities concluded: “Coincidence is excluded.”

The research method

They started with official channels. What they found was instructive.

The team obtained an internal email showing that all state interior ministries were instructed to give uniform responses to questions about drone sightings. Coordinated stonewalling.

“We were trapped in a bureaucratic maze,” Michèle Borcherding told the audience. “The federal states closed ranks. Nobody felt responsible. We got passed from one spokesperson to the next, and it felt like the left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing.”

But here’s the thing that made them dig harder: “The answers we got were nearly identical. That everyone blocked us like that triggered the thought: something’s there.”

So they kept digging. And obtained the classified BKA reports that authorities didn’t want public.

Tens of thousands of data points

Clara Veihelmann led the ship tracking analysis. They used Global Fishing Watch (globalfishingwatch.org) to pull AIS data—the automatic identification system that broadcasts ship positions.

“We analyzed tens of thousands of data points,” Veihelmann explains. “We looked closely at ship data in the North Sea and Baltic Sea.”

They were looking for anomalies. Cargo ships move from A to B. Efficiency matters. So when the team saw a ship track that looked like someone had scribbled furiously with a purple marker—loops, circles, ten days of chaos in Kiel Bay instead of a clean transit line—the audience laughed at how absurd it looked.

Experts confirmed: absolutely not normal for a coastal freighter that’s supposed to be making money delivering cargo.

The three ships

The HAV Dolphin

Specifications: 88.32m long, 12.50m beam. Built 1993. Flag: Antigua & Barbuda. Owner: HAV Shipping AS (Norway).

The HAV Dolphin is “the most striking example of all,” the team concluded.

From late March to late April 2025, the ship spent nearly a month at the Pregol Shipyard in Kaliningrad—a facility with documented ties to the Russian military and Rosatom.

Then it sailed to Kiel Bay. May 1-10: the ship sat there for nine days, exhibiting chaotic movement patterns. During exactly this period, drones were spotted on three separate days over defense shipyards 25 kilometers away. Observers noted the drones appeared to come from the direction of the Baltic Sea.

The BKA’s own classified report notes: “A container ship under the flag of Antigua & Barbuda had been anchoring in Kiel Bay since May 1, 2025, with a recent extended stay in Russia.”

The HAV Dolphin has been inspected three times by German and Dutch authorities. Each time: nothing found.

But here’s what the team learned from security sources: those inspections were “superficial“ and “symbolic in nature.” Not all containers were opened. You can’t properly search a freighter like that without many investigators and more time, they were told.

Classified security documents reveal another detail: “During personnel inspection, an additional watch officer was found on board who behaved conspicuously during the inspection.” The captain claimed he was there for training purposes.

The crew? Entirely Russian.

And another incident: In early June, a drone was spotted inside the military security zone at a naval radio station between Ramsloh and Rhauderfehn—used for communication with German submarines and NATO ships. It flew over for about two minutes before disappearing. Seventy kilometers away, the HAV Dolphin had been anchored in the Ems estuary for three days.

The Lauga

Specifications: 102.50m long, 16.40m beam. Built 1994. Former name: “Ivan Shchepetov.” Flag: Russia. Owner: Idan Shipping Company, St. Petersburg.

Night of May 16-17, 2025. The Lauga transits through the North Sea, escorted by the German Federal Police vessel Potsdam.

At approximately 1 AM, the police vessel reports: “Seven drones detected around the deployment ship.” The drones circle both the Russian freighter and the German police ship for hours. Three eventually depart. Four keep circling. Eventually, the police vessel breaks off its escort.

Belgian customs later searched the Lauga in Zeebrugge. All eleven crew members—Russian citizens to a man—were questioned. No drones found.

But the Lauga’s history is telling. Summer 2024: the ship called at Tartus, Syria—Russia’s only naval base in the Mediterranean, where Russian submarines dock.

After the Belgian search, the Lauga sailed to St. Petersburg and docked at the Petrolesport terminal—owned by Delo Group, which is 49% owned by Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear corporation.

The ship’s owner, Idan Shipping Company, is run by Andrei Selyanin. Documents show Selyanin’s other companies openly advertised working for Rosatom in 2024. The team found evidence of earlier Rosatom connections in additional documents.

The HAV Snapper

Specifications: 88.16m long, 12.50m beam. Built 1991. Flag: Bahamas. Owner: HAV Shipping AS (Norway)—same company as the HAV Dolphin.

On the evening of May 16, the HAV Snapper sailed out to a position off the Dutch island of Schiermonnikoog. Two hours before the first drones were spotted over the Lauga and Potsdam, she took up station. She stayed for four days.

Distance from the Lauga incident: 115 kilometers. Within drone range.

The HAV Snapper was serviced at the Pregol Shipyard in Kaliningrad from August 4-29, 2023—the same facility where the HAV Dolphin spent nearly a month before the Kiel incidents.

HAV Shipping told the journalists that Pregol is “a reputable shipyard used by many European shipping companies.” Perhaps. But Pregol has documented connections to both the Russian military and Rosatom.

The Rosatom Thread

The team traced ownership chains, maintenance records, corporate connections. Multiple threads led to Rosatom—Russia’s state nuclear corporation, responsible for nuclear weapons and the submarine program. Rosatom also operates the Atomflot fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers.

Then they found a 2024 Rosatom presentation. It showed an orange-and-blue drone on the helipad of a massive red icebreaker in an Arctic landscape.

Rosatom’s drone specifications:

• Speed: 140 km/h

• Range: at least 200 kilometers

• Maximum altitude: 2.5 kilometers

• Equipment: video cameras, thermal imaging

• Can launch and land on ships

Officially, Rosatom uses these drones for Arctic sea route surveillance. Conditions in the North Sea and Baltic? Far more favorable than the Arctic.

The HAV Dolphin was 25 kilometers from the Kiel drone sightings. The HAV Snapper was 115 kilometers from the Lauga incident. The naval radio station incident: 70 kilometers from the HAV Dolphin.

All well within Rosatom drone range.

The chase

“At this point it was clear to us,” Borcherding says. “We don’t just want to see these ships as data on our screen. We have to get one of them in front of our own eyes.”

They tracked the HAV Dolphin to a French Atlantic port. Called the harbor authority. Got confirmation: the ship would stay until 7 PM the next day.

They flew to Paris. Rented a car. Drove five hours to the coast.

The ship was gone.

What followed was a 2,500-kilometer pursuit from France through the Netherlands to Belgium. The HAV Dolphin was “unpredictable.” Left ports early. Sometimes crawled. Then suddenly sped up. Changed destination data. Then deleted its destination entirely.

It never reached Antwerp. Instead, it parked on a sandbank off the Belgian coast near Ostende. Then it started circling—25 kilometers offshore, directly in front of a Belgian military base.

The team finally caught up.

We droned back

They flew their own drone over the HAV Dolphin.

From the air: 88 meters long, 12 meters wide. Open cargo hold with grid covers, typical for multi-purpose freighters. German security sources confirmed what they’d suspected: the crew was exclusively Russian sailors.

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Germany’s domestic intelligence agency) told the team:

“Russian intelligence services deploy so-called low-level agents for espionage, sabotage, and other disruptive measures. These ‘pocket money agents’ or ‘disposable agents’ operate for small sums in the interest of hostile intelligence services without belonging to them. They’re used for comparatively simple operations. Unlike regular staff, they’re expendable—exposure is accepted as a cost of doing business.”

The profile: young men with unstable social circumstances and financial difficulties. Recruited online via messenger services and social media. Financially motivated, sometimes ideologically aligned with Russia.

The Munich prosecutor found no evidence linking airport drone incidents to disposable agents. But the intelligence service confirms the tactic exists and is actively used.

What intelligence services say

European intelligence services assess the three documented ships as operating “with high confidence“ on behalf of Russian interests. Their movement profiles are “very conspicuous” and show “little evidence of commercial activity.”

The German Interior Ministry’s official response: “German security authorities are aware of the ‘shadow fleet’ phenomenon. The issue is being continuously addressed within respective legal jurisdictions. (...) Reports of drone overflights remain consistently high. (...) Involvement of foreign state entities in a non-quantifiable portion of drone overflights is to be presumed.”

“Non-quantifiable portion.” “To be presumed.” That’s intelligence-speak for: we know it’s happening, we can’t prove exactly how much, but we’re not going to say that publicly.

19 Correlations

The team’s final tally: they could draw 19 temporal and geographic correlations between drone sightings and the positions of the three ships.

When drones appeared over northern Germany, a pattern emerged: often, multiple ships exhibited suspicious behavior simultaneously. Movement data showed suspicious patterns over multiple days.

HAV Shipping CEO Petter Kleppan responded to the team’s findings: “HAV has exclusively large, established European companies as customers. We transport dry goods from port to port—steel, curbs, grain, scrap. Typical invoice: about €50,000. We have no Russian customers and generate no revenue from Russia. HAV has ‘self-sanctioned’—we don’t transport goods to or from Russian customers, and we don’t work with Russian brokers.”

What they proved and didn’t prove

“Our trail leads to Russia,” the team concludes. “Not beyond doubt, but it’s currently the most probable explanation. We systematically laid both things side by side: the secret reports about drone incidents and the routes of the ships. You can at least recognize a pattern.”

They didn’t find a drone on any ship. They can’t prove causation. What they established:

• Ships with Russian crews exhibited anomalous behavior near German military installations

• Multiple ships from the same owner positioned suspiciously during the same incidents

• These ships have connections to Russian military-linked facilities (Pregol, Rosatom, Tartus)

• 19 correlations between ship positions and documented drone incidents

• Russia’s state nuclear corporation operates ship-launched drones with sufficient range

• Official inspections were “symbolic”—not all containers opened

• European intelligence assesses these ships as “with high confidence” working for Russia

Why this matters

When the presentation ended, the boss of the paper in the front row spoke up. “I’ve rarely seen anything this good,” she said. “I hope you’re sufficiently proud of yourselves. This is really outstanding. I have goosebumps.”

She was right. Seven students, five weeks, publicly available ship tracking tools, and a willingness to drive 2,500 kilometers on a hunch. They produced a more coherent picture of Germany’s and Netherlands drone mystery than months of official hand-wringing and coordinated stonewalling.

Track them yourself

The ships are still sailing. And you can watch them. The AIS data is still updating. Go find them.

As I write this (December 11, 2025), the HAV Snapper is in the Aegean Sea, underway from Volos to Thessaloniki, Greece. Speed: 8 knots. Course: 327°. Draught: 4.3 meters. Expected arrival: 07:30 local time.

I pulled this from MarineTraffic three minutes ago. You can do the same.

HAV Snapper identifiers for tracking:

• IMO: 9001813

• MMSI: 311014800

• Call sign: C6XN4

• Flag: Bahamas

• AIS transponder: Class A

Free tracking tools:

• MarineTraffic.com — Search by vessel name or IMO number. Free tier shows current position; paid tiers show historical tracks.

• VesselFinder.com — Similar functionality, good for cross-referencing.

• Global Fishing Watch (globalfishingwatch.org) — What the Axel Springer team used. Better for historical analysis and bulk data.

• Kpler — Professional-grade commodity and shipping intelligence. Subscription required but powerful.

The IMO number is key—it’s the ship’s unique identifier that doesn’t change even if the vessel changes names, flags, or owners. The Lauga used to be the “Ivan Shchepetov”. Same IMO number.

Set up alerts. Watch for anomalous behavior. When a cargo ship that should be moving from A to B starts circling for days in the Baltic, you’ll know.

That’s the point of OSINT: find the story in public data.

Below, members only, full presentation.